When he arrived at Shad in 2008, Yassen Tcholakov was already envisioning a future in healthcare—though the exact path wasn’t yet clear. Surrounded by a diverse group of talented peers, he spent that summer exploring big ideas and collaborating on meaningful challenges. The experience helped to shape his journey, leading him to a career in medicine and impactful work in public and global health, including consulting on the Paris Climate Agreement.

“I really enjoyed meeting so many people at Shad, spending time discussing different and interesting projects. It was great to have time to just brainstorm around different issues with the freedom to think in a structured yet open space with students who were interested in things like I was.”

The experience came at an ideal time for Yassen, providing him the chance to explore post-secondary and career opportunities when he was making important decisions about his future. It helped him to better understand what he wanted to do and the impact he hoped to have through his career choice.

“Shad came at a very formative time in my life. It gave me the chance to connect with people from diverse backgrounds and interests, to build friendships, and to exchange ideas. That experience is incredibly valuable for students as they begin thinking about their next steps.”

Yassen was studying health sciences at CEGEPs, a unique system of publicly funded colleges in Quebec that offers the first level of post-secondary education, when he attended Shad. He fell in love with the process of identifying a problem and working out how to solve it in the best, most effective way. His first real-world opportunity to put those lessons into practice came shortly after Shad when he started a school internship at Hydro-Québec.

“At Hydro-Québec, I helped develop their pandemic plan—researching best practices, connecting with other energy providers, and building a framework for implementation. It was my first real glimpse into how health policy becomes action.”

The experience informed Yassen’s decision to attend medical school at the University of Montreal, where he was able to engage his love of collaborative work through the International Federation of Medical Students Association (IFMSA), eventually becoming a member of the association’s Supervising Council that worked as a kind of Board of Directors advising IFMSA on really important health-related issues. This role gave Yassen a breadth of experience dealing with important health issues alongside groups of professionals with the power to effectuate change and implement policy.

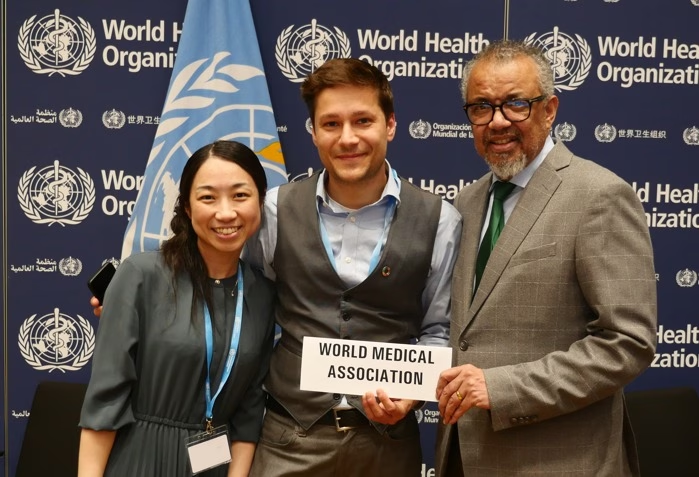

“Through IFMSA, I was able to represent medical students in United Nations meetings and in World Health Organization (WHO) meetings on issues important to medical students. I also interned at the World Health Organization and got to meet the climate change team, gaining a lot of insight into what the WHO team was working on.”

It was during his final year of medical school when Yassen had the opportunity to represent IFMSA as part of the consulting body for the Paris Climate Agreement. Many of the arguments made for constraining global warming to 2 degrees Celsius related to the adverse effects on human health, and so it was important for medical professionals to act as consultants when formulating the wording of the Paris Agreement’s protocols.

“We were trying to answer the question ‘where can health be included in the text’ in ways that mattered. In the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which is the organization that was negotiating the Paris Agreement, its first article says that we’re doing this in part to protect people’s health from the impacts of climate change. So, our goal was identifying the areas of the negotiations which would have the greatest impact on health and trying to use health arguments with negotiators to influence what should be included in writing in the Agreement.”

Following this experience, Yassen decided he wanted to pursue a public health track in medicine, having greatly enjoyed the challenge of working to find solutions to larger health issues facing the public with a group of dedicated peers.

“Public health physicians do the same work as a doctor in terms of evaluating the health of patients, making diagnoses, and giving recommendations for how to get better or how to maintain health, but for entire populations. Doctors working in public health try to see what the biggest burdens of health are and then try to deploy interventions to prevent them at the population level. It’s incredibly collaborative and involves a lot of problem solving to maintain the health of the community.”

Yassen was finishing his residency rotation in public health during the COVID-19 pandemic, which provided him real-time practice managing a health crisis. The experience helped to bolster Yassen’s interest in infectious disease epidemiology and the role it plays in public health. He had done part of his public health residency in Nunavik, a remote area in Northern Quebec, and so when a position became available to lead the region’s infectious disease team, Yassen jumped at the opportunity.

“Nunavik is a small public health department that oversees a large, remote area. I was interested in working here because I thought it would be more challenging, and I would have to have more innovative solutions for problems.”

The Nunavik region presents a unique set of challenges given the area’s demographics and location. The Nunavik public health department consists of 14 separate communities not connected by land, consisting of a population that is 90% Inuit.

“The Nunavik region is a very challenging setting because there’s a lot of systemic inequity still in the health care and social systems in the region. There are infectious diseases here that are pretty much non-existent elsewhere. We have tuberculosis (TB) rates that kind of put Canada to shame because they’re higher than even some of the poorest countries in the world with the least resources.”

Many of these health problems are the result of the socioeconomic disparities of the region. Often families live below the poverty line in crowded spaces in areas that have limited access to the resources that help promote good health.

“These communities, they’re not connected by land to each other. They’re connected by planes or by boat during summer months, and during winter you can go by ski, which doesn’t provide for effective transport of personnel or supplies. So that means that there are fewer things available. Even for very simple things, many people have to travel for health services, stay for days outside of their own community before they can come back.”

His desire to remedy these inequities fuels Yassen’s work to implement solutions to the public health problems facing his patients. He spends his days working to improve health access for the people in the area, implementing policies that give more healthcare agency to the local population.

“We’re placing a strong emphasis on empowering the local population by involving them more directly in decision-making and resource allocation wherever possible. Some of our current projects are focused on creating job opportunities specifically for people from the local community. At present, most healthcare services are delivered by professionals from outside the region. We’re working to change that by developing positions that are accessible to local residents—roles that don’t require degrees unavailable in Nunavik or necessitate travel for education. These new opportunities will allow individuals who have completed their schooling locally to enter the workforce, significantly improving access to care for residents.”

Yassen’s team is also working on developing things like wastewater surveillance so that data can be used to deploy the right public health interventions to the right communities. Drawing on the lessons he took away from his time at Shad and the experiences that followed, Yassen sees his role as an opportunity to have a positive impact and improve the lives of the people living in the communities he serves.

“The fact that there are a lot of inequities with respect to the rest of the population of Canada demonstrates the work there is to do in Nunavik, and my job is to figure out how those inequities can be resolved. I believe there are things that we can do to restore a level of health similar to the rest of the country. So, each day we’re here to find opportunities to make a difference on some of those things, to meet those challenges and improve lives.”